Heads

Much has been said about the horrors of war. I have learned firsthand there are horrors within the horrors.

My platoon was restricted to providing tactical advice to rebel groups in Syria. Progress was remarkable in pushing back the elements of ISIS that had control of smaller towns along the main road to Kobane.

We could hear the sound of small arms fire, and the return fire of automatic weapons that were the Coalition’s gift to the rebels. Then silence as we waited for the call from Abdul Ashif, our Comms guy. He was to monitor the search for hidden ISIS elements and, when all clear, send a radio message for us to come ahead.

We were hardened to the expected landscape of dead terrorists strewn about the streets and the bodies of their snipers hung over window sills.

And more, in every town at least one wall held the Arabic phrase that our translator said was “death will not be easy.” That was reputed to be the calling card of an extremist group that clung to an ancient mysticism.

My job was to stay back of my unit, an eye to what should have been cleared behind us, as we were always mindful of surprise. There had been a techie brief before we deployed, hinting at progress in giving the Marines, and eventually the rest of us, small mobile robots to do follow-up surveillance. With no robots yet, the platoon had to make do with my best efforts.

Our Captain signaled the go-ahead from Ashif, and we entered a town as torn up as others we had the misfortune to go through in recent days. We stepped over the ISIS bodies and reported back to Command what had to be viewed, from the perspective of war, as another accomplishment.

Ashif radioed that his group was moving forward again, already a mile out of that town and toward another. Almost out ourselves, we were going through a courtyard between some shops and a small mosque when we were confronted by the sight we dreaded most.

There were bodies of civilians haphazardly flung, one atop another, not the usual forced lying down in rows for execution, as news photos often showed. What we had was the aftermath of a last orgy of murder, before ISIS had to run.

We only saw adults, but knew from experience there were probably the corpses of children, too, hidden below. We had time, as it was best to keep some distance between ourselves and our rebel friends, and the medics did what was needed to see if anyone was still alive. No one was. It was slow work in any case, as we were always wary of booby traps.

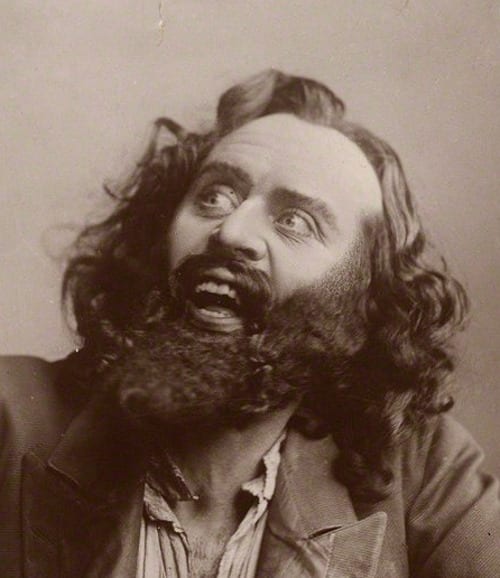

My instincts and my job had me looking behind us. No problems there, but what I saw down a short alley to my left will be with me forever. In that pathway, where both walls proclaimed the mystic mantra “death will not be easy,” there was an iron gate, and on its points were stuck the heads of three poor souls, old men with beards.

I had heard of such a thing. The victims were possibly dead before beheading, and that thought helped me cope.

I was mesmerized, so I didn’t say anything, but just approached the gate. The heads on either side had eyes open, glassy dead, the kind of eyes I had seen many times.

Something about the middle head was odd.

As I got closer, I realized what it was. Its eyes, also wide open, had seemed to do the impossible.

Had seemed to blink at me.

I was no more than six feet from it and suddenly desperate to confirm hallucination. That drew me forward, until I was just short of being nose-to-nose with the thing.

I saw the pupils contract and widen.

Something in me yielded, accepted the horror for what it was. I made myself blink, three times slowly.

The head blinked back, three times slowly.

If death would not be easy, I could make it so. I pulled my pistol and shot, how many rounds I can’t say, but the head and those on either side were obliterated. My comrades, I’m told, dragged me away to sedation. Recuperation and discharge have left me fine, almost.

I’m not able to step on an ant or cockroach without having to step on it again, and again and again just to be sure. Just to be sure.